This is the second in a two-part blog series on the Emotet malware. The first part was posted on February 27, 2020.

A Look Under the Hood

The binary that contains the Wi-Fi attack vector was only recently analyzed, but when it was, researchers realized that it had an April 2018 timestamp, has a hard-coded C2 IP address known to be used by Emotet, and that it had been submitted to VirusTotal in May 2018. This could mean that this attack vector has been live and unnoticed for two years.

There is also evidence that it works to hide itself from security researchers by deliberately keeping a low profile. The wlanAPI exploit for Wi-Fi enumeration is not triggered if it’s running on a VM or automated sandbox with no Wi-Fi adapter.

The good news is parts of the attack do not operate efficiently. Even though the enumeration process identifies the Wi-Fi authentication method (WEP, WPA PSK, WPA2 PSK, WEP, or Open), the malware will still run through the brute force attempts even if the SSID is Open, the PSK is cached, or the client is already associated to the SSID.

CLICK TO TWEET: CommScope’s Heather Williams continues her Emotet blog series, explaining what’s under the hood and how Ruckus solutions can help with security.

Evolving Story

As of Friday February 21, 2020, Emotet's operators deployed the Wi-Fi spreader as a module (the earlier version appears to have been a module test). They then began distributing it at an incredibly rapid pace. This updated module ensures that the dropped binary on the remote host is the most updated version. It is also acting in a stealthier manner, which may make it harder to detect. Instead of arriving on the system as a self-extracting RAR file, the worm module arrives by itself and pulls down the service.exe file after it establishes contact with the C2 server.

Sophisticated Phishing

Emotet operators have also begun spam runs using an email template posing as a “Kyoto Coronavirus” notification. As with their other campaigns, these spam runs contain malware in attached files or links. Opening the files allows Emotet to infect the computer. This is not new functionality but rather an evolution of their phishing campaigns. Its effectiveness is directly related to the credibility associated with the template, which is in Japanese and includes information relating to the recent coronavirus outbreak and symptoms.

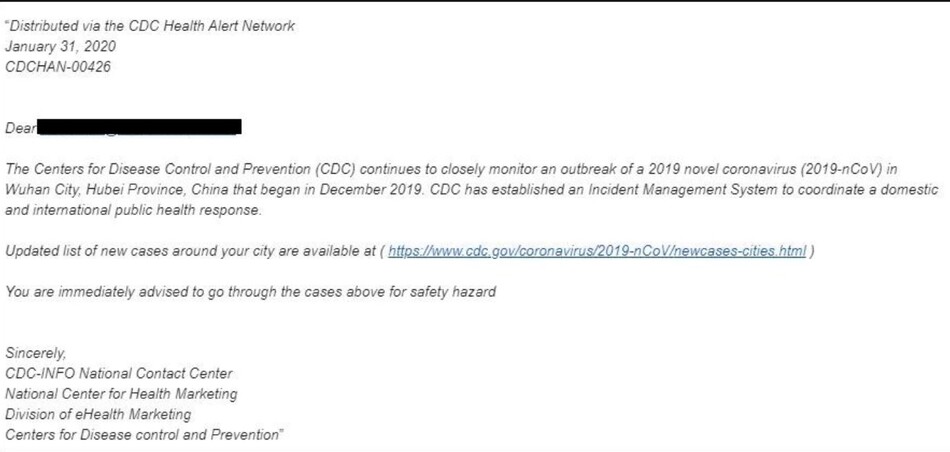

The example below is a real phishing email. Although it is not an Emotet example, it is an excellent example of just how sophisticated Emotet and other malware phishing campaigns have become. How many people would consider clicking the link?

Figure 1: Coronavirus Phishing Email

How Ruckus Helps

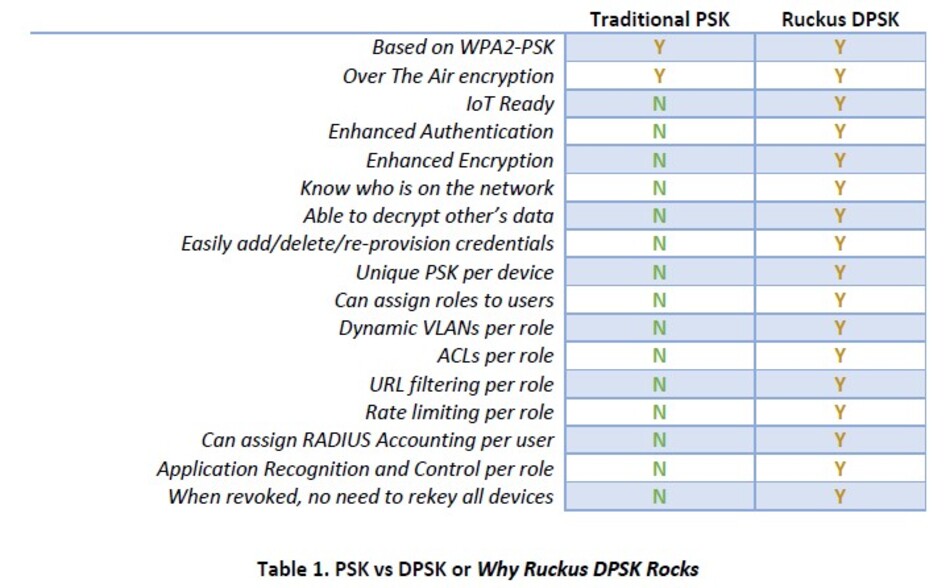

The key to this new attack vector is finding both Wi-Fi networks and clients associated with those networks that have weak passwords. Ruckus customers can substantially mitigate the effectiveness of the Emotet attempts by taking advantage of Client Isolation and our Dynamic PSK and Cloudpath secure onboarding capabilities to help protect them from this new attack vector. Ruckus Cloudpath will create a complex, WPA2-Enterprise DPSK password, which is unique to each device and can be expired at any time. This is supported on all Ruckus SmartZone controller options, Unleashed, and ZoneDirector. Ruckus SmartZone also provides other mitigation against brute force attempts against a PSK. Multiple login attempts like a brute force attack result in the user being blacklisted for a configurable amount of time.

Figure 2: PSK vs Ruckus DPSK

Note: DPSK and Cloudpath cannot protect against Emotet’s phishing campaigns. A good endpoint detection and response solution and an effective security awareness/anti-phishing training program are both highly recommended.

Summary

Emotet is a dangerous and versatile malware with a sophisticated core and regularly evolving phishing attacks. Its most successful infection method is still accomplished by email campaigns; however, it now has a Wi-Fi attack vector in its toolbox and they are actively evolving those capabilities.

For a detailed breakdown of Emotet’s new attack vector, see the blog by Binary Defense, the security researchers who first discovered it running in the wild.